In scientific

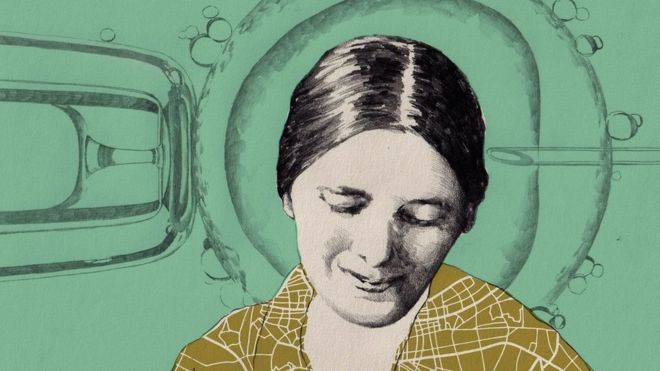

discovery textbooks, the researcher spends the night alone in his laboratory

doing research. Suddenly there is a window of the mind, an apple falls on the

head, a lightning strikes, a poisonous petri dish appears. And then there's

Eureka! But Mary Mencon's story is slightly different. One Tuesday night in

February 1944, a 43-year-old lab technician stayed up all night for his

eight-month-old daughter. She calls it a "living tissue sample"

because her daughter's teeth were just starting to come out.

The next morning, like every week for the past six years, Mankin went to his

lab. It was Wednesday when he poured a freshly washed egg into a solution of

sperm in a glass and prayed that the two would become one. As a technician for John Rock, a fertility

expert at Harvard, Mankin's goal was to make the egg fertile outside the human

body. This was the first step in Rock's project to treat infertility.

Infertility has always been a mystery to doctors. John Rock especially wanted

to help women whose uterus was healthy but had an ovarian defect because he had

seen in clinical infertility cases that one in five women had this defect. was

present. Mankins usually kept sperm and

eggs together for 30 minutes. But that did not happen that day. Years later, he

told a reporter what had happened. He said: "I was so tired and sleepy

watching the game of sperm with the egg under the microscope that I forgot to

look at the clock and when I suddenly looked at the clock, an hour had passed.

In other words, I can say that my success after almost six years of failure is

due to a nap at work rather than a mental window opening.

When she arrived at the lab on Friday, she saw a miracle. The cells had melted

and were dividing and they saw the first glimpse of the fertilization of human

sperm in a glass. Menken's achievements

ushered in a new era for reproductive technology. The beginning of an era in

which infertile women began to conceive, babies began to be placed in test

tubes, and scientists began to look at the very early stages of human life. In

1978, the world saw the first tube-born baby named Louis Brown, who was born

with IVF, meaning in vitro fertilization. IVF soon became a big business. In

2017, there were 284,385 attempts to have children through IVF in the United

States, which resulted in 78,052 children like Brown.

However, the way he told his story, Manken's success was not a coincidence.

Like the other great moments of discovery, there was years of research, hard

work, and the perseverance of repeating the same experience over and over

again. He then co-authored 18 research

papers, including two historical reports in the journal Science on his first

success. But unlike his co-author Rock, his name did not go unnoticed. History

does not agree with Manken's role. They have been described in many ways.

Sometimes she was called a technician, sometimes a research assistant,

sometimes a biologist, sometimes Dr. Mankin, sometimes Miss. In a way, they are

all right. Theresa Woodruff, head of reproductive science at the Feinberg

School of Medicine at Northwestern University and a professor of maternal and

child health, said she was more than just a rock assistant. "I think they

should be considered John Rock partners and peers," Woodruff said. She was

not just a helping hand or a technician, as people say, but an intellectual who

did her job. Rutgers University historian Margaret Marsh agrees. "Rock was

basically a clinicist," she says of Mankin, "she was a scientist with

a scientific mind and a true scientist who believed in the importance of

scientific protocol."

While writing Rock's autobiography, published in 2008, Marsh found the story of

Manken. He co-authored a book, Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive

Revolution, with Wanda Runner.

But looking back, she regrets that she only described Mankin as a research

assistant (much credit goes to Mankin in Marsh and Runner's latest book, The

Pursuit of Parenthood). Is). "If I were to reconsider, I would say she was

scientifically minded," she says. She was not the only one who obeyed.

One day in 1900, an egg met a sperm and they met. These two countries were

divided into two cells, then into four and then into eight cells. And nine

months later, on August 8, 1901, Mary Friedman was born in Riga, Latvia. While

she was still walking, her family emigrated to the United States, where her

father earned so much money as a doctor that he spent his childhood in comfort,

where he worked as a housemaid. She later recalls how she was amazed to hear

stories that science would soon find a cure for diabetes. He made a

promising start to his scientific career, graduating from Cornell University in

1922 with a degree in histology and comparative genetics, and the following

year with a master's degree in genetics from Columbia University, while

teaching biology and physiology for a short time in New York. ۔

But when he decided to follow in his father's footsteps and

enter medical school, he encountered the first obstacle. He was rejected by two

of the country's top medical schools. "I don't know why," she

recalls. I think the main reason was my personality. In fact, it was because of their gender. At

that time no medical school accepted women and what they did was strictly

enforced quotas. In 1917, a dean said that Cornell called for a ban on girls so

that his school would not have too many female candidates.

To protect it, she kept dripping liquid into the container.

For hours late at night, she ate sandwiches with one hand, worked with eggs,

and dripped liquids with the other. She

sadly recalls that the first egg slipped out of her hands, which was "the

first abortion in a test tube." But they did it three more times and

developed a two-stemmed zygote with a two-celled zygote. They tied him to a

glass with red and blue tape and sent him to the Carnegie Institution of

Washington in Baltimore. Mencan said he was "a model of our pride and our

joy" because he "proved without a doubt that we had eggs." By

the time they got there, Rock and Mankin had received letters from hundreds of

infertile women who had asked them if science could cure them. Menkin was now ready to become a reproductive

scientist who would take fertility further. Then they planned to fertilize an

egg with four cells, then eight and then who knows how many? But then something happened that neither he

nor Rock had thought of. Her husband lost his job. As a wife and mother of a

child, she moved with him to Duke University in North Carolina, where IVF was

seen as a scandal, and a doctor called it a "rape in vitro" test

tube. Said to rap.

Without Mancin's expertise, IVF research in Boston stalled.

Since then, no rock assistant has been able to fertilize a single egg in the

tube. Talking to school children, he

expressed surprise at the process of mixing sperm and ovum in the tube: 'When

you think about how small this ovum is and when it is free from its follicle

Happens and then falls into relatively turbulent physical activity so don't you

wonder if he doesn't lose? How does this little thing find a place to go? In the case of the ovum, the body of the

female undergoes remarkable changes and carries it forward. The part of the web

of fingers that joins at the end of the fallopian tube hardens, fills with

blood, and pulls the egg into the tube, where the tiny fur called the cilia

pull the egg further in. They even take it to the ovary. In Mankin's case, two things led him to

research fertility. One is their constant devotion and then a little bit of

luck. Her husband's job took her from

place to place, but she continued to look for opportunities to pursue eggs and

labs. He knocked on the doors of well-known researchers working on reproduction

and asked to write his introduction to Rock.

A professor of history at Northeastern University who has written about

Mancin's services in reproductive science says: "It could have been done

by someone who was so passionate about going into a lab and saying, 'Oh, John

Rock Worked with. Will I have a chance in the lab? It requires a lot of

confidence and a strong desire to work, if not boldness. But in 1945, Mankin wrote to Rock from North

Carolina that "opportunities to work on the egg here are still

discouraging." Even without the lab, however, she continued to collaborate

with Rock from afar. In 1948, the two wrote a joint research paper on their

first success in IVF, which was published in the journal Science, with Mencon

as the first author.

But she soon encountered some difficulties with her research

in the field of IVF. She prevented a divorce from Valley, who tortured her in

front of her children, Lucy and Gabriel, and stopped paying her Had done In a

September 1948 letter, he wrote: "I think it will be very traumatic, and

it will be very difficult for Gabriel in particular to bear the stigma of

divorce." But when her husband's

behavior worsened, she decided to divorce. "I don't want to commit suicide

so slowly," he wrote the following month. He approached a lawyer, filed

for divorce and obtained permission to keep Lucy in his custody. As a single mother, she had difficulty

meeting all her needs. Lucy, who had epilepsy and was always ill, had to be

taken to a psychiatrist and doctors. When Mankin was allowed to use the lab for

free on holiday nights, it became impossible for him to do so. In the early 1950's, Mankin returned to

Boston to enroll Lucy in a special children's school. After that she started

working in the lab with Rock again but a lot has changed in this decade. At

that time, reproductive work was not to produce more babies in the tube, but to

prevent more babies from being born. Rock

and his lab's main mission now was to promote easy contraception. This was the

work that led to the historic approval of birth control pills in 1960.

Other institutions, including Harvard, only accept female

students during wartime. The first women's class at Harvard began in 1945. Marie Walsh writes in her book, Doctors

Wanted: No Woman's Need to Apply, that in a college debate on the 'women's

question', a faculty member said that letting female students come means that

women's primary job is to have children and their It would be a violation of

the basic biological law of Prosh. Instead,

she married Willie Manken, a medical student at Harvard. Mary Manken worked as

an assistant to her husband during his education until she received another

degree in Secretarial Studies from Simmons College. Taking advantage of her closeness to

education, she completed courses in bacteriology and embryology and also helped

her husband in the lab. There he met Harvard biologist Gregory Punks, who later

worked with Rock to develop contraceptive pills.

Pincus became infamous as a Frankenstein scientist because

he made a fatherless rabbit that was fertilized in a cage and grew up healthy

and jumping. They assigned the mankin to extract two key hormones from the

pituitary gland, which he had to insert into the female rabbit's uterus to

produce extra eggs. Manken did it

skillfully, but he had to stay in the lab for a short time. In 1937, Pincus'

tenure was not extended and he returned to England, possibly leading to

Mankin's job. John Rock soon emerged on

the horizon as a fertility specialist who wanted to take research into the

animal of the pincus into clinical research. In an unsigned editorial in the

New England Journal of Medicine, she wrote: "What a blessing a closed tube

can be for a barren woman." Mankin

applied for a job in his lab, which was approved. "She was smart, strong

and hardworking and fit for rock work," Marsh said. "He was an

intelligent, shrewd, answer-seeker, but he had no patience for the lab's

endeavors," Rock wrote.

Luckily, her frustration with the rock lab led to Mary's

success.

Every Tuesday morning at eight o'clock, Mankin would gather

outside the operating room in the basement of a free charity hospital for

low-income women in Brooklyn, Massachusetts. She recalls that luckily one day

Rock would give her a small piece of an ovary that would be the equivalent of a

small hazel nut or a gun. She would take him up the stairs to the fourth floor

and run to her lab. There she would open it and look for the precious eggs in

it. This was not an easy task. Although

it is the largest cell in the body, the human egg is still smaller than the one

point we apply to a letter. Most people need a microscope or magnifying glass

to see them and yet they only have a deeper perspective. For Mankin, it was a universe. She would

identify the egg with her own eyes and tell him just by looking at it that it

was bad or normal. She proudly calls herself Rock's 'egg chaser'.

One after the other, that is, every week, Mankin continued

to follow the same routine. Go for ovulation on Tuesdays, mix them with sperm

on Wednesdays, pray on Thursdays and look into a microscope on Fridays. Every

Friday, when they look in the incubator, they find a single-celled

non-fertilized egg, along with clusters of dead sperm. He repeated this process

138 times in six years. Even on this

lucky day in 1944, when they opened the door of the incubator, they cried out

for rock. Talking to the school children, he later said, "Even that day,

as usual, they were trying to get a real baby for a mother at a hospital on the

other side of town." "We called them ... When they saw what was in

the box, they turned white like a ghost.

The lab was full of spectators because 'everyone ran to see the youngest

human child. Manken did not let the egg disappear from his sight. She wrote in

a draft for one of her talks that she was "afraid to let go of this

precious thing that was the interpretation of a six-year-old unfulfilled dream." To protect it, she kept dripping liquid into

the container. For hours late at night, she ate sandwiches with one hand,

worked with eggs, and dripped liquids with the other. She sadly recalls that the first egg slipped

out of her hands, which was "the first abortion in a test tube." But

they did it three more times and developed a two-stemmed zygote with a

two-celled zygote. They tied him to a glass with red and blue tape and sent him

to the Carnegie Institution of Washington in Baltimore. Mencan said he was "a

model of our pride and our joy" because he "proved without a doubt

that we had eggs." By the time they got there, Rock and Mankin had

received letters from hundreds of infertile women who had asked them if science

could cure them. Menkin was now ready to

become a reproductive scientist who would take fertility further. Then they

planned to fertilize an egg with four cells, then eight and then who knows how

many? But then something happened that

neither he nor Rock had thought of. Her husband lost his job. As a wife and

mother of a child, she moved with him to Duke University in North Carolina,

where IVF was seen as a scandal, and a doctor called it a "rape in

vitro" test tube. Said to rap. Without

Mancin's expertise, IVF research in Boston stalled. Since then, no rock

assistant has been able to fertilize a single egg in the tube. Talking to school children, he expressed

surprise at the process of mixing sperm and ovum in the tube: 'When you think

about how small this ovum is and when it is free from its follicle Happens and

then falls into relatively turbulent physical activity so don't you wonder if

he doesn't lose? How does this little thing find a place to go? '

In the case of the ovum, the body of the female undergoes

remarkable changes and carries it forward. The part of the web of fingers that

joins at the end of the fallopian tube hardens, fills with blood, and pulls the

egg into the tube, where the tiny fur called the cilia pull the egg further in.

They even take it to the ovary. In

Mankin's case, two things led him to research fertility. One is their constant

devotion and then a little bit of luck. Her

husband's job took her from place to place, but she continued to look for

opportunities to pursue eggs and labs. He knocked on the doors of well-known

researchers working on reproduction and asked to write his introduction to

Rock. A professor of history at

Northeastern University who has written about Mancin's services in reproductive

science says: "It could have been done by someone who was so passionate

about going into a lab and saying, 'Oh, John Rock Worked with. Will I have a

chance in the lab? It requires a lot of confidence and a strong desire to work,

if not boldness. But in 1945, Mankin

wrote to Rock from North Carolina that "opportunities to work on the egg

here are still discouraging." Even without the lab, however, she continued

to collaborate with Rock from afar. In 1948, the two wrote a joint research

paper on their first success in IVF, which was published in the journal Science,

with Mencon as the first author. But she

soon encountered some difficulties with her research in the field of IVF. She

prevented a divorce from Valley, who tortured her in front of her children,

Lucy and Gabriel, and stopped paying her had done In a September 1948 letter,

he wrote: "I think it will be very traumatic, and it will be very

difficult for Gabriel in particular to bear the stigma of divorce." But when her husband's behavior worsened, she

decided to divorce. "I don't want to commit suicide so slowly," he

wrote the following month. He approached a lawyer, filed for divorce and

obtained permission to keep Lucy in his custody. As a single mother, she had difficulty

meeting all her needs. Lucy, who had epilepsy and was always ill, had to be

taken to a psychiatrist and doctors. When Mankin was allowed to use the lab for

free on holiday nights, it became impossible for him to do so.

In the early 1950's, Mankin returned to Boston to enroll

Lucy in a special children's school. After that she started working in the lab

with Rock again but a lot has changed in this decade. At that time,

reproductive work was not to produce more babies in the tube, but to prevent

more babies from being born. Rock and

his lab's main mission now was to promote easy contraception. This was the work

that led to the historic approval of birth control pills in 1960. As the Rocks approached their ultimate goal,

Mary was working behind the scenes as their 'Literary Assistant'. She explored

research topics ranging from the freezing of Japanese sperm to infertility in

horses. (In response to one of his questions, he wrote: 'Dear fun, in the midst

of the world's troubles, I'm glad you're interested in the infertility of

horses!') The research paper was written on the topic of whether women's

menstruation can be stabilized by light and whether a warming jackstrap can

temporarily keep men infertile.

Although his subsequent dissertations were far from his

original goal, Mankin was ultimately collaborating for him. Like rock, they

explored the mysteries of reproduction and added to the knowledge of science.

She also cared about 'infertile women' and was proud of her contribution to the

technology that would one day help such women become mothers. But he was not personally interested in using

IVF. "I never do it because I don't think its right to do that," he

told reporters. You risk too much ... You can make a monster. More than that, he was interested in solving

the riddles of fertilization outside the womb. In vitro work was an opportunity

for him to be represented in a wide range of scientific projects, but the

completion of this career derailed. It's

hard to imagine what Mary Manken would have done if her life had been

different, if she hadn't married Wally or if she had a doctorate. It can only

be said that their commitment and circumstances forced them into a special box.

Even at the height of her scientific career, she was

described as a new mother with a missing mind who found success. But to see him

as a scientist of his own, one must look at his careful notes, strict

protocols, and his well-researched bibliography. Of course, she was not just a slave to

anyone's orders.

With thanks BBC Urdu

0 Comments